Quick Answer

If you’re choosing flooring for Irish new builds vs period homes, your subfloor matters more than style. New builds typically have insulated slabs, radon barriers, and screeds that demand moisture testing and flatter tolerances. Period homes often have suspended timber or breathable constructions that can rot or trap damp if you “seal” them with the wrong products. Pick your floor after you confirm moisture, deflection, levels, ventilation, and (in some areas) radon.

Key Takeaways (for homeowners, self-builders, renovators)

- New builds: expect slab + insulation + screed + radon detailing; the big risk is fitting too soon (moisture still in the screed).

- Period homes: expect suspended timber, shallow voids, uneven levels, and damp pathways; the big risk is trapping moisture and starving ventilation.

- Moisture testing is non-negotiable for wood, LVT, and adhesives (guessing is how floors “mysteriously” fail).

- Apartments: acoustic performance is a system (resilient layers, perimeters, details) not a single “soundproof underlay”.

- UFH: easiest on new screeds, hardest in retrofits because of height build-up, thresholds, and mixed subfloors.

- Radon: in mapped higher-risk areas, radon measures (membranes and often standby sumps) affect floor build-ups and service penetrations.

- FBS Flooring approach: choose the floor after the subfloor survey, moisture testing, and a prep plan, not before. (fbsflooring.ie)

The best flooring choice in Ireland is the one that matches your structure: slabs and screeds want stable, moisture-tolerant systems; suspended timber wants breathable build-ups and controlled movement. If you select flooring before checking moisture, flatness and deflection, you can end up paying twice, once for the “nice floor”, and again to remove it.

New Build vs Period Home in Ireland: What “Different” Actually Means

In Irish housing talk, “new build” and “period home” aren’t vibes; they’re shorthand for how the floor is built, and therefore how it behaves when you heat it, ventilate it, and walk on it.

What counts as a “new build” in Ireland?

Most people mean post‑2000 (Celtic Tiger estates to today), and especially post‑2011 and post‑NZEB-era homes, where insulation and airtightness levels are much higher. Practically, this usually means:

- Ground floors: concrete slab, insulation, radon/DPM layer, screed (often with UFH).

- Intermediate floors: timber joists (timber frame) or concrete slabs, with attention to fire/sound depending on dwelling type.

- Ventilation systems: designed ventilation matters more because “accidental draughts” are engineered out.

What counts as a “period home” in Ireland?

Typically:

- Georgian (roughly 1714–1830) terraces and townhouses

- Victorian/Edwardian (roughly 1837–1910) redbrick terraces and villas

- Early 20th-century cottages and town housing

Plus a massive chunk of Irish stock from the 1930s–1970s that behaves “older” in moisture and ventilation terms.

Common floor realities:

- Suspended timber floors with airbricks/vents (and sometimes vents that were blocked by years of paving).

- Uneven levels and patch repairs (bit of concrete here, timber there).

- No modern DPC continuity, so moisture can travel in ways that surprise people — especially once you retrofit insulation and airtightness. (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie)

Why this definition matters

Because the same flooring product can be:

- Perfect over a dry, flat, insulated screed, and

- A disaster over a damp, bouncy suspended timber floor.

In Irish new builds, the key flooring constraint is usually residual moisture in screeds and radon membrane detailing. In period homes, the key constraint is often ventilation and movement in suspended timber floors, plus unevenness. Choosing flooring without identifying the subfloor type is like choosing tyres without knowing whether you’re driving on tarmac, gravel, or bog road.

The 7 Structural Differences That Should Decide Your Floor (Not Fashion), Flooring for Irish New Builds vs Period Homes

Here’s the core idea: floors fail when structure + moisture + movement aren’t respected. These seven differences are what installers in Ireland repeatedly see causing callbacks, disputes, and heartbreak.

1) Moisture and vapour movement: “breathable” vs “sealed”

- New build slabs are generally designed to be sealed against ground moisture (DPM/radon barrier, insulation, screed).

- Older floors often managed moisture by evaporation and ventilation (especially suspended timber). When you add impermeable layers, you can redirect moisture into timber ends, joists, skirtings, or plaster.

Practical consequence:

- Impermeable finishes (some vinyl systems, certain coatings) can be fine on a modern slab if moisture levels are proven, but risky on an older “breathing” build-up unless you redesign the whole system.

2) Flatness and levels: modern tolerances vs real-life old floors

New builds should be flatter (not always, but should). Period homes often have:

- dips near chimney breasts,

- slopes to the front,

- patched sections from old plumbing/electric works.

Practical consequence:

- Click systems (laminate, click LVT, floating engineered) are less forgiving of lumps and dips.

- Glue-down systems can cope better, but only if the substrate is properly smoothed and moisture-controlled.

3) Deflection and point loads: bounce breaks brittle finishes

A suspended timber floor can feel “grand” underfoot yet still have enough micro-movement to crack:

- tiles,

- stone,

- microcement,

- brittle levellers.

Practical consequence:

- If you want tile/stone on timber, you may need structural stiffening (joist upgrades, additional decking, engineered tile backer systems). That is a structural decision, not a flooring-only decision.

Safety note (keep it sane): If you’re altering joists, trimming structural timbers, or removing sleeper walls, consult a competent engineer or qualified professional. Floors are not the place for guesswork.

4) Thermal upgrades (Part L context): insulation changes the drying and moisture behaviour

Retrofitting insulation can make surfaces warmer (good) but also changes where moisture condenses and dries. Irish guidance recognises that approaches designed for new work may be impractical or risky in older buildings and that alternatives may be needed.

Practical consequence:

- A period home floor upgrade plan should include ventilation and moisture strategy, not just “throw insulation at it.”

5) Acoustics (Part E context): especially for apartments and multi-unit

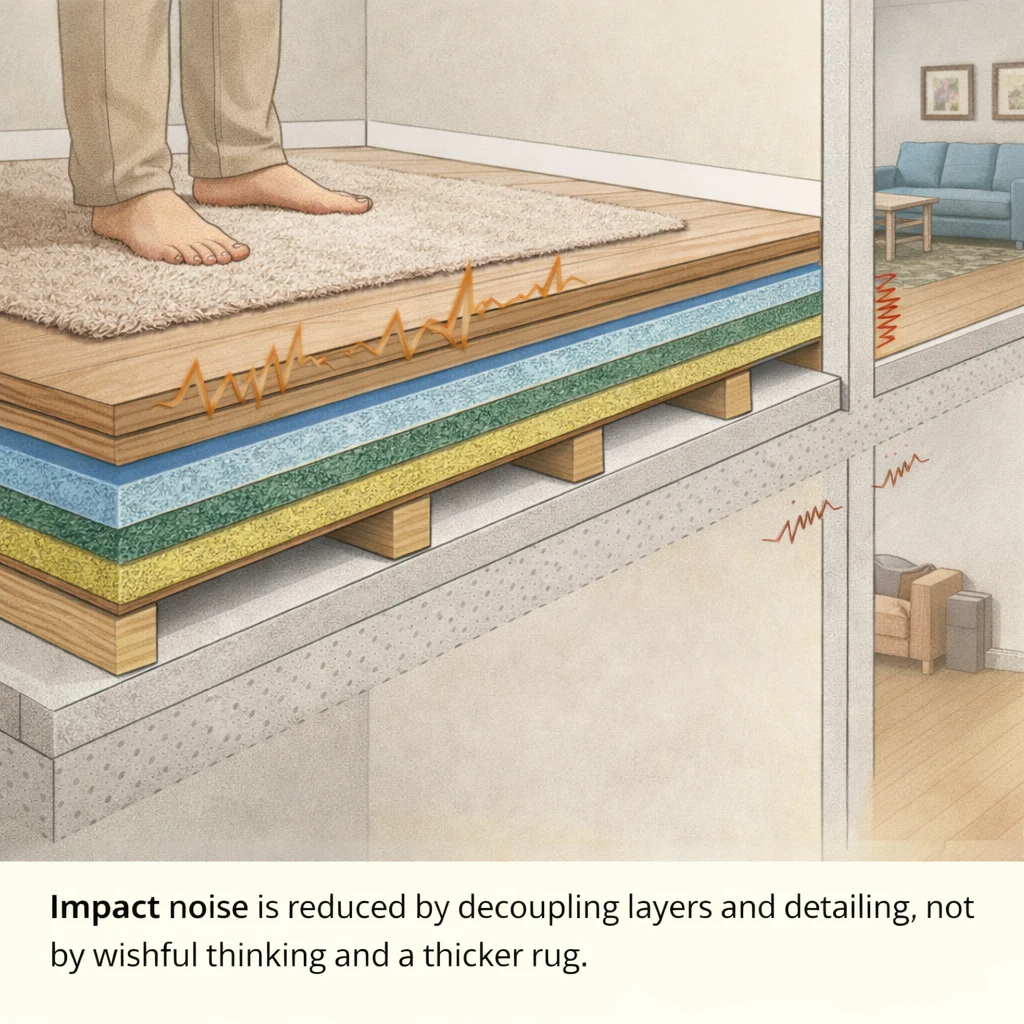

For apartments (and some conversions), you’re designing to airborne and impact sound targets — and those targets are defined in guidance.

Practical consequence:

- “Acoustic underlay” is not a magic product; it’s part of a tested build-up, including perimeter isolation strips, correct densities, and correct floor type.

2-Image (acoustics): Floating floors and resilient layers

- Direct image URL:

sandbox:/mnt/data/fbs_img08_acoustic_resilient_layer.png - Source page URL:

N/A (original illustration) - Licence/usage note: CC BY 4.0 — Original illustration created for this article (FBS Flooring, 2026)

- Alt text: Apartment acoustic floor build-up Ireland resilient layer Part E sound impact

- Caption: Impact noise is reduced by decoupling layers and detailing, not by wishful thinking and a thicker rug.

6) Fire considerations: materials + building type matter

Fire guidance differs by building type (dwelling houses vs apartments/common areas). For dwellings, Ireland has specific Technical Guidance Documents for fire safety. (gov.ie)

Practical consequence:

- In apartments and common escape routes, floor finish requirements can be more demanding — don’t assume a domestic product is acceptable everywhere.

7) UFH compatibility: stable heat wants stable floors

New builds increasingly pair UFH with low-temperature heat sources. Ireland’s ventilation guidance also highlights the need to control moisture and pollutants in modern, more airtight homes. (Government Assets)

Practical consequence:

- Some floors work beautifully with UFH (tile, many engineered woods, glue-down vinyl systems), while others reduce output or increase movement risk.

The most common reason floors fail in Irish new builds is fitting over a screed that’s still too wet, especially in winter when heating/ventilation isn’t fully running. The most common reason floors fail in period homes is trapping moisture or ignoring movement in suspended timber floors. Both problems are preventable with a subfloor survey and moisture testing.

Irish New Builds: Typical Floor Build-Ups and What They Allow

Ground-bearing slab + insulation + screed (the most common)

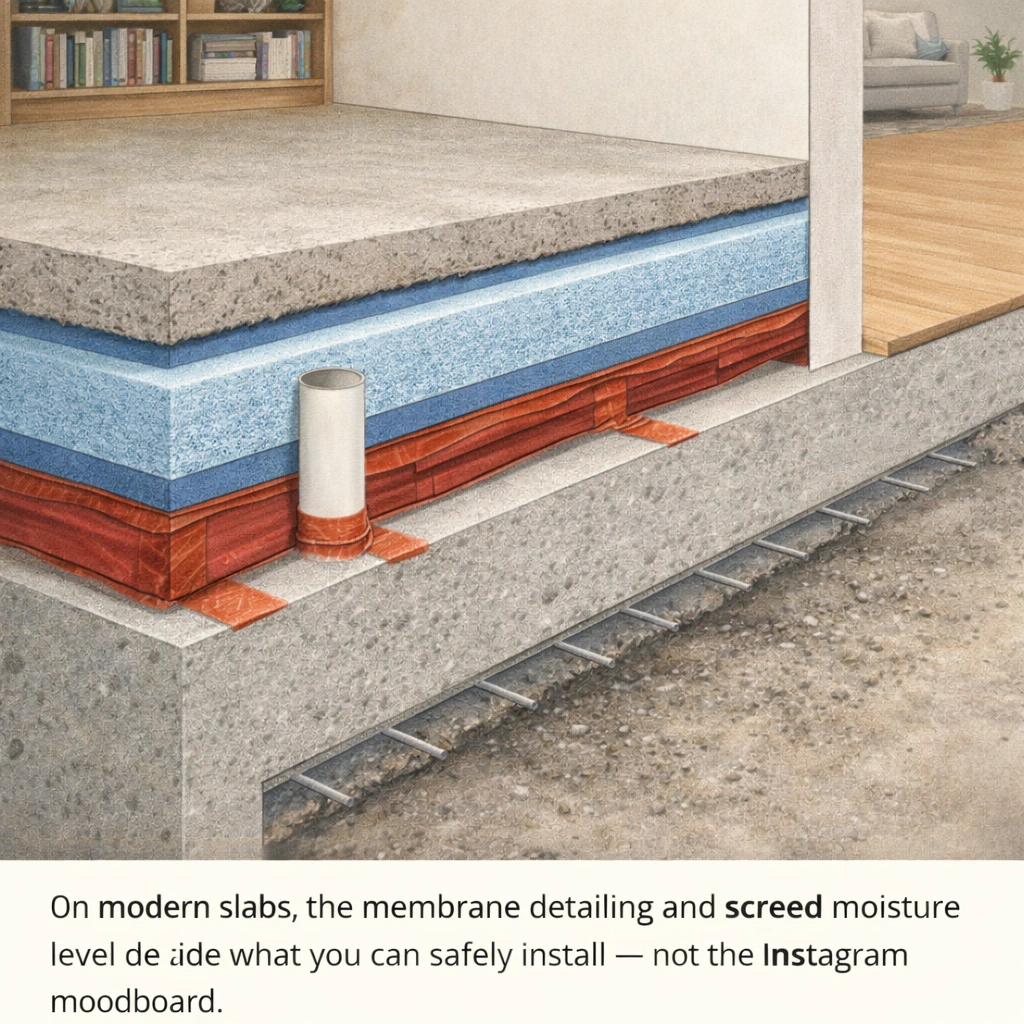

A common Irish new-build ground floor build-up is: hardcore → slab → radon/DPM membrane → insulation → screed → floor finish, with careful detailing at perimeters and service penetrations. Guidance for moisture and radon protection is set out in Part C documentation.

What this build-up allows (when dry and flat):

- Porcelain/ceramic tile and stone (with correct prep)

- Engineered wood (often the sweet spot for stability)

- LVT (click or glue-down; glue-down needs best prep)

- Carpet (easy, but UFH output depends on tog/thermal resistance)

What commonly goes wrong in Ireland:

- Houses are “weather-tight” but not fully heated/ventilated yet; screeds dry slowly in Irish humidity. Installers often find that a screed that looks dry still measures too high for timber or resilient adhesives.

Timber frame intermediate floors (movement + acoustics)

In many Irish timber frame houses, intermediate floors are timber joists with decking, sometimes with acoustic layers depending on design and dwelling type.

Practical flooring implications:

- Floating floors can amplify “drumminess” if underlays are wrong.

- Tiles/stone need careful design to manage deflection and movement.

Apartments: acoustic compliance is not optional

TGD E sets out guidance and targets for airborne and impact sound insulation.

If you’re in an apartment, your flooring choice may be constrained by:

- the certified acoustic floor build-up,

- the allowed finish types,

- and the need to avoid hard connections at perimeters.

You can usually install engineered wood or LVT in an Irish new build once the screed is proven dry enough and flat enough for the product system. The biggest mistake is rushing: adhesives and timber are unforgiving. Plan for moisture testing, levelling/smoothing where needed, and UFH commissioning before the floor goes down.

How FBS Flooring fits into this decision (real-world workflow):

FBS Flooring typically recommends choosing the product after a subfloor check: identify slab/screed type, check flatness, confirm UFH presence, and test moisture, then specify the correct underlay/adhesive system. FBS supplies and fits common Irish choices like laminate, SPC, engineered wood, and click vinyl/LVT, and can budget labour realistically once prep is known.

- Best flooring for kitchens and bathrooms in Ireland

- Subfloor preparation guide, levelling compounds, primers, and smoothing

Irish Period Homes: Suspended Timber, Breathability, and Uneven Reality

Period floors in Ireland can be beautiful, wide boards, old pine, stone flags, but they’re rarely “plug and play”.

Suspended timber floors: ventilation is everything

Suspended timber floors rely on underfloor airflow to manage moisture risk. Part C guidance addresses resistance to moisture and relevant construction principles.

Common Irish on-the-ground issues installers see:

- airbricks blocked by raised external ground levels, tarmac, or garden beds

- shallow voids with rubble and damp soil

- joist ends embedded in damp masonry

- past “repairs” using concrete that bridged moisture pathways

Stone flags, limecrete and “breathable floor build-ups”

In older cottages and some townhouses, you may find stone flag floors or solid floors that were historically more vapour-open. Irish heritage guidance frequently stresses compatibility and moisture management for traditional buildings.

Practical consequence:

If you replace a breathable build-up with a fully sealed modern concrete system without redesigning moisture control, you can drive damp into walls and finishes.

Uneven levels and thresholds

Period homes often have:

- lower floor-to-ceiling heights,

- door frames that can’t be easily trimmed,

- stairs that you really don’t want to rework.

Flooring implication:

- Thin build-ups matter. Sometimes the “best” floor is the one that meets levels without forcing a chain reaction of joinery changes.

In a Victorian or Georgian terrace with a suspended timber floor, the safest flooring choices are usually those that tolerate movement and don’t trap moisture — for example, certain engineered timber systems or carpet, once ventilation and moisture risks are addressed. Tiling can work, but only with a stiffness and build-up strategy designed for timber deflection. (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie)

Flooring Options Ranked by Subfloor Type (With a Decision Matrix)

This is where most online articles go vague. Let’s not. Below are practical decision tools you can actually use.

Visual 1 (required): Simple ASCII cross-section — New build slab vs suspended timber

NEW BUILD (typical) PERIOD HOME (common)

-------------------------------- --------------------------------

Floor finish Floorboards / finish

Screed (often UFH) Joists + void (ventilated)

Insulation Airbricks/vents to outside

Radon/DPM membrane Bare soil / oversite (varies)

Concrete slab (Sometimes no modern DPC)

Hardcore/subsoil Ground moisture managed by airflow

Table 1 (required): Subfloor type × best flooring × avoid/risks × prep needed

| Subfloor type (Ireland) | Best flooring types | Avoid / risks | Prep needed (typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| New build slab + screed | Tile/porcelain; engineered wood; glue-down LVT; carpet (UFH-aware) | Solid wood too early; click floors on uneven screed; anything without moisture test | Moisture test (RH); smoothing/levelling; UFH commissioning cycle; correct primers/adhesives |

| Timber frame intermediate floor | Engineered wood; carpet; some LVT systems | Tile/stone without stiffness design; “drummy” floating floors with wrong underlay | Deflection check; acoustic detailing where required; levelling/decking upgrades as needed |

| Apartment separating floor (concrete or timber system) | Finish allowed by certified acoustic build-up (often engineered/LVT/carpet) | DIY changes that break acoustic/fire spec | Follow Part E targets and the specified resilient layer/perimeter details (Government Assets) |

| Suspended timber ground floor (period) | Engineered wood (correct system); carpet; some floating systems with vapour-aware underlays | Tile/stone without stiffening; impermeable “caps” trapping moisture | Ventilation check; fix bounce; replace rotten boards; consider vapour-open approach where appropriate (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie) |

| Mixed/patchwork subfloors (common in renovations) | Often glue-down solutions after full prep; sometimes carpet | Click systems bridging different materials; brittle finishes over moving junctions | Isolation/decoupling strategies; full smoothing; movement joints |

Flooring material deep-dive (Irish-specific cautions)

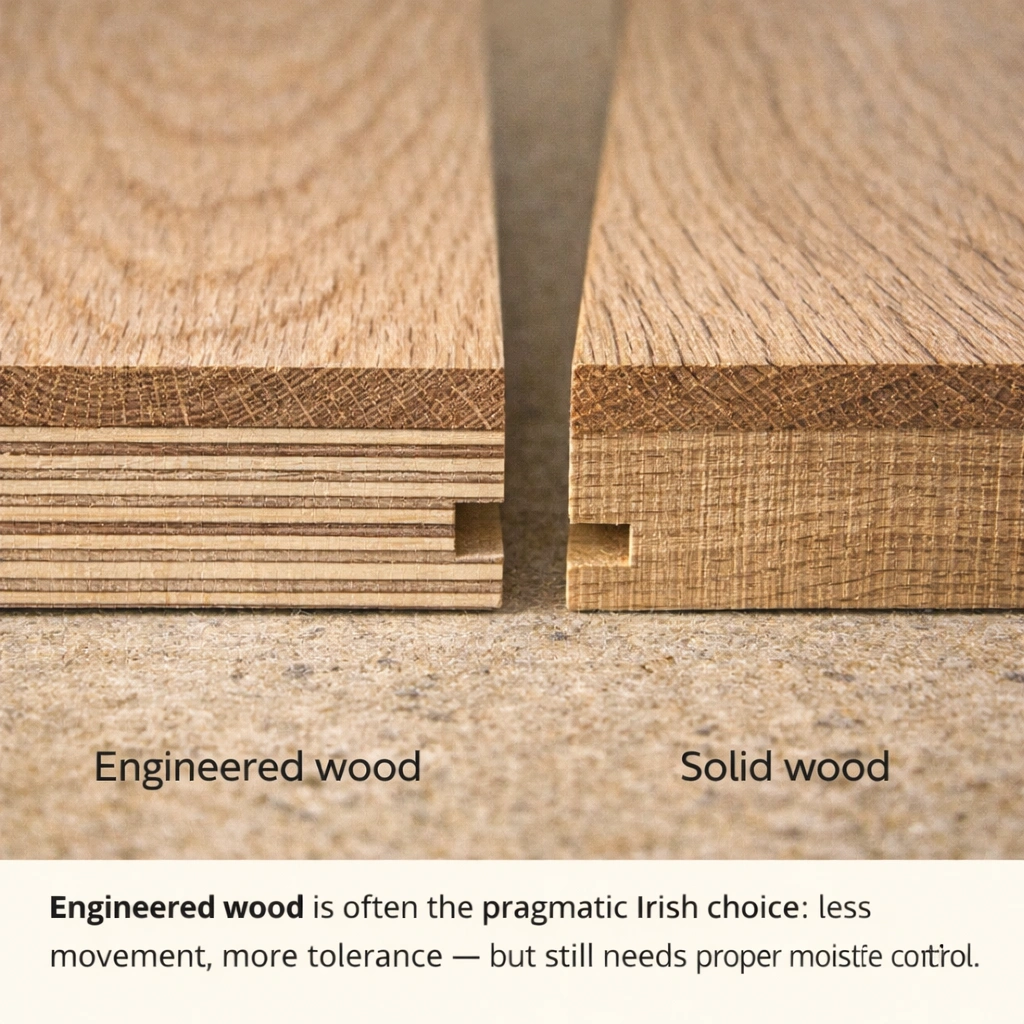

Engineered wood (often the safest “timber look” in Ireland)

Engineered boards are built to reduce seasonal movement (compared with solid). That stability helps with:

- UFH cycles,

- Irish humidity swings,

- and “almost flat” subfloors once properly prepared.

When to choose engineered wood

- New build screeds once moisture is proven acceptable (don’t guess).

- Period homes where you want timber character but need better stability than solid.

Avoid engineered wood if…

- You can’t meet the moisture limits in the product/adhesive spec,

- The subfloor is too uneven, and you’re not prepared to level,

- You want to “float” it over a damp suspended floor without addressing ventilation.

Solid wood (beautiful, but least forgiving)

Solid timber can absolutely work in Ireland — but it’s the diva of floors:

- It needs stable indoor conditions,

- reliable subfloor dryness,

- correct expansion detailing.

Best use-cases: heated, well-controlled interiors; properly dried subfloors; period renovations where you’re matching existing joinery.

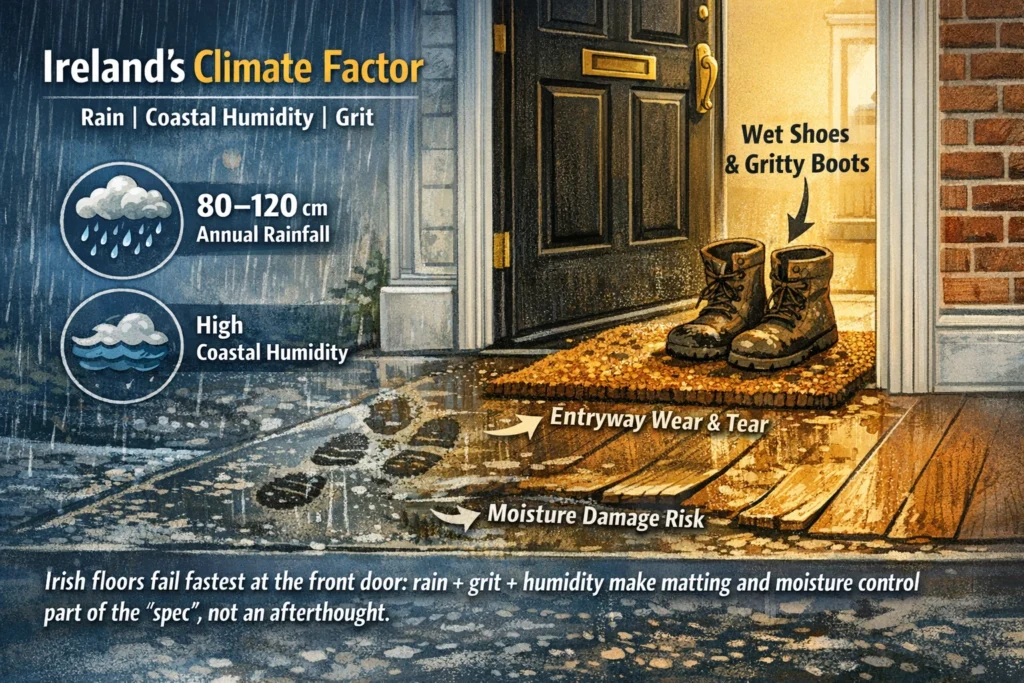

Big Irish gotcha: coastal humidity and wet entryways can drive movement if matting and ventilation aren’t managed.

Laminate

Laminate is popular in Irish estates because it’s budget-friendly and durable — but it’s a floating system that needs:

- flatness,

- correct underlay,

- good perimeter detailing.

FBS Flooring supplies and fits laminate as a common Irish option, but the subfloor prep still decides whether it will feel solid or “clicky”. (fbsflooring.ie)

LVT / Vinyl (click vs glue-down)

- Click LVT: faster, more forgiving, but hates unevenness and can telegraph dips.

- Glue-down LVT: best feel and detail, but demands excellent smoothing and moisture control.

When to choose glue-down LVT in Ireland

- kitchens, hallways, rentals, and anywhere you want a tough, stable finish once the substrate is properly prepared.

Avoid LVT if…

- moisture testing is skipped, or

- you’re using a system not rated for the moisture condition present.

Porcelain/ceramic tile and stone (plus decoupling)

Tile is brilliant on slabs and UFH. On timber or mixed substrates, you need a movement strategy.

Carpet + underlay

Carpet is still one of the best “problem solvers” in:

- bouncy period floors,

- upstairs noise control,

- bedrooms where warmth matters.

But with UFH, total thermal resistance matters — too much tog and your UFH becomes an expensive lukewarm suggestion.

Cork, linoleum, bamboo (sustainability + moisture reality)

Cork and linoleum can be superb in Ireland for comfort and sustainability, if moisture and flatness are controlled.

Polished concrete / microcement overlays (Instagram vs physics)

Overlays can crack if the substrate moves or shrinks — and Irish humidity can slow curing/drying. These finishes demand:

- stable substrates,

- moisture control,

- and realistic expectations about hairline cracks.

Visual 2 (required): Decision flowchart (ASCII)

START

|

|-- What subfloor do you have?

| |-- Slab + screed -----> Moisture test (RH) -----> UFH?

| | | |

| | | |-- Yes: prefer tile/engineered/glue-down LVT

| | |-- Too wet: delay / dry / moisture system (per spec)

| |

| |-- Suspended timber ----> Check vents + void + bounce ----> Want tile/stone?

| | |

| |-- Yes: stiffness + tile system design (engineer/tiler spec)

| |-- No: engineered/carpet/other tolerant finishes

|

|-- Apartment? ----> Follow certified acoustic build-up (Part E targets)

|

FINISH: Choose product system (adhesive/underlay) + plan thresholds + expansion + transitions

Visual 3 (required): Scoring matrix (1=poor, 5=excellent)

Rule: This is a starting point — moisture, flatness and movement can swing scores up or down.

| Flooring type | New build slab+screed | Suspended timber (period) | Timber intermediate floor | Apartment (acoustic constraints) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcelain/ceramic tile | 5 | 2 | 2–3 | 3 (if allowed) |

| Stone | 4 | 1–2 | 2 | 2–3 |

| Engineered wood | 4–5 | 4 | 4 | 4 (if build-up compliant) |

| Solid wood | 3 (when dry) | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Laminate | 3–4 | 3 | 3–4 | 3 |

| LVT click | 3–4 | 3 | 3–4 | 3–4 |

| LVT glue-down | 5 (with prep) | 3–4 | 4 | 4 (if compliant) |

| Carpet | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Cork/linoleum | 4 (when dry/flat) | 3–4 | 4 | 4 |

If you want one “safe default” across many Irish homes, engineered wood is often it — provided moisture is controlled and the substrate is properly prepared. Tile is the safest on modern slabs, but the riskiest on bouncy suspended timber. Carpet is the quiet hero for older upstairs floors and noise control, especially in apartments. (Government Assets)

Internal link suggestions (placeholders):

- Engineered wood vs laminate, what Irish buyers should check

- Acoustic underlays explained for apartments

Underfloor Heating: New Build Easy Mode vs Period Home Hard Mode

New build UFH: designed for it (usually)

New build UFH is typically installed in screed with insulation below, which is the ideal set-up for consistent heat output.

Retrofit UFH: it can work, but it’s a coordination project

In period homes, UFH often means:

- raising floor levels,

- trimming doors,

- adjusting stairs and skirtings,

- and managing mixed substrates.

Table 2 (required): UFH compatibility table (with thermal resistance notes)

| Flooring type | UFH compatibility | Max tog / thermal resistance notes (rule-of-thumb) | Install notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porcelain/ceramic | Excellent | Very low resistance | Use suitable adhesive; allow for movement joints; commission UFH cycle before sensitive finishes |

| Stone | Excellent | Low–moderate (depends on thickness) | Heavier loads; check substrate strength and crack control |

| Engineered wood | Good–excellent | Keep boards thinner / low resistance | Use UFH-rated engineered; follow gradual heat-up/cool-down; expansion gaps |

| Solid wood | Mixed | Higher movement risk | Only if moisture stable; prefer narrower boards; UFH-rated spec essential |

| Glue-down LVT/vinyl | Excellent | Low | Needs best smoothing + moisture compliance |

| Click LVT/laminate | Good | Underlay can add resistance | Use UFH-rated underlay; watch flatness; avoid thick foams |

| Carpet + underlay | Mixed | Total tog can get high | Choose UFH-suitable carpet/underlay; output reduces as resistance rises |

Note: Exact thermal resistance limits vary by UFH system design and manufacturer. Treat the table as guidance, confirm with your UFH designer and flooring spec.

Best UFH flooring in Ireland is usually porcelain/ceramic tile, then glue-down LVT, then UFH-rated engineered wood because they transfer heat efficiently and stay stable. Thick underlays and high-tog carpets reduce output, and solid timber needs the tightest moisture control. Always commission UFH properly before installing moisture-sensitive floors.

Internal link suggestions (placeholders):

- Flooring choices for heat pumps and UFH in Irish homes

- How to plan thresholds and trims in UFH retrofits

Moisture, Radon, and Airtightness: The Irish Trio That Trips People Up

This trio is why Ireland-specific advice matters. You can’t copy‑paste generic “UK tips” and expect a perfect outcome, because local ground conditions, radon mapping, and common build-ups change the risk profile.

Moisture: test it, don’t vibe-check it

Industry guidance commonly uses RH testing (and similar methods) to confirm suitability for floor coverings — and manufacturers set limits for their adhesives and products.

What FBS Flooring sees in practice:

Even when a new build looks finished, a closed-up house with limited heat/ventilation can hold moisture in the screed far longer than homeowners expect, especially through Irish winter.

Radon: not everywhere, but serious where it is

EPA Ireland provides radon information and mapping, and Ireland’s building guidance addresses radon protective measures (including membranes and, in certain areas, standby sumps).

EPA guidance uses a reference level of 200 Bq/m³ for indoor radon concentration.

Flooring implication:

- Your radon barrier (often combined with the DPM function) is part of the floor system — don’t puncture it with sloppy fixings, and treat service penetrations as critical details. (Government Assets)

Airtightness + ventilation: modern comfort needs designed airflow

Ireland’s ventilation guidance is explicit: adequate ventilation should limit moisture (condensation/mould) and pollutants. (Government Assets)

Flooring implication:

- Low-VOC adhesives and good ventilation during curing matter more in airtight homes.

- Moisture produced indoors (cooking, showers, clothes drying) can drive humidity swings that affect timber and some resilient floors.

In Ireland, radon and moisture control start below your feet. If you’re in a mapped higher-radon area, radon measures (membranes and often standby sumps) influence floor detailing and penetrations. Separately, screeds can stay wet longer in our climate. The safe approach is: confirm radon strategy, then moisture test before installing sensitive finishes. (Government Assets)

Cost, Timeline, and Disruption (Ireland-specific)

Let’s be blunt: subfloor prep is what usually blows budgets — not the floor you picked.

What flooring installation costs look like in Ireland (ranges, not promises)

FBS Flooring’s Ireland-specific labour ranges (2026) show typical installation labour bands by flooring type, and highlight that levelling, moisture protection and trims often decide final cost. (fbsflooring.ie)

Table 3 (required): Budget ranges (€ / m²) — materials + installation + prep allowances

Disclaimer: These are indicative Irish ranges. Product grade, room shape, access, VAT status, and subfloor condition can move them significantly. Always price from a site survey.

| Flooring type | Materials (€/m²) | Install labour (€/m²) | Typical prep allowance (€/m²) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminate | 12–35 | 15–25 (fbsflooring.ie) | 0–15 | Underlay/flatness sensitive |

| Engineered wood | 35–120 | 20–45 (fbsflooring.ie) | 5–25 | Glue-down costs more but feels best |

| Solid wood | 60–180 | 40–65 (fbsflooring.ie) | 10–35 | Highest moisture risk/care needed |

| LVT click | 20–45 | 18–28 (fbsflooring.ie) | 5–25 | Can telegraph unevenness |

| LVT glue-down | 25–60 | 35–55 (fbsflooring.ie) | 10–30 | Smoothing is key |

| Carpet | 12–60 | 6–12 (fbsflooring.ie) | 0–10 | Great on imperfect floors |

| Tile/porcelain | 20–90 | 40–70 (fbsflooring.ie) | 10–35 | Waterproofing in wet rooms adds cost |

| Stone | 70–200 | 60–100 | 15–45 | Weight + substrate quality matter |

Hidden costs that catch Irish homeowners out

- Levelling/smoothing: often €8–€25/m² depending on depth and drying time. (fbsflooring.ie)

- Moisture mitigation: primers/barriers when allowed by the floor system (cost varies widely).

- Door trimming + thresholds: especially in UFH retrofits and older houses.

- Skirting decisions: scotia vs remove/refit skirting. (fbsflooring.ie)

- Disposal: old carpet/tiles/adhesive removal.

Timeline reality (new builds vs period homes)

- New builds: the timeline is often dictated by screed drying + testing + UFH commissioning.

- Period homes: the timeline is dictated by discovery (rot, damp, unevenness) and making the structure right before the finish.

Two Ireland-based mini case studies (typical scenarios)

Typical scenario 1: Dublin new build semi (slab + UFH + engineered wood goal)

Homeowners choose engineered wood early. Site survey finds smoothing needed and moisture still high for the adhesive system. Plan changes: delay install, improve heat/ventilation, retest, then glue-down engineered in living areas and tile in wet areas. Result: better feel underfoot, fewer movement issues, and realistic handover timing. (fbsflooring.ie)

Typical scenario 2: Cork Victorian terrace (suspended timber + blocked vents + “I want tiles everywhere”)

Survey finds shallow void and vents partially blocked by external levels. Floor is bouncy in the hall and front room. Strategy: restore ventilation routes, repair timber, stiffen where needed, then use engineered timber in living spaces and tile only where the build-up is engineered for it. Result: character retained, damp risk reduced, and fewer cracks. (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie)

Mistakes to Avoid

New builds: the greatest hits of avoidable pain

- ☐ Fitting timber/LVT before confirming screed moisture (no test, no mercy).

- ☐ Ignoring flatness and hoping the underlay will “fix it”.

- ☐ Turning UFH on full blast to “dry it out” without a commissioning plan.

- ☐ Damaging radon/DPM membranes at thresholds or service penetrations.

- ☐ Forgetting expansion gaps and transition joints.

- ☐ Not planning trims/thresholds early (especially with tile + timber combinations).

Period homes: different building physics, different mistakes

- ☐ Blocking airbricks/vents or sealing a suspended floor without a moisture plan.

- ☐ Tiling onto bouncy timber without stiffening and a proper tile system design.

- ☐ Levelling with incompatible materials that trap moisture in traditional build-ups.

- ☐ Raising floor levels and creating door/stair/threshold domino problems.

- ☐ Treating mould/damp as a “flooring problem” instead of a moisture/ventilation problem.

Conclusion: A Practical “Choose Your Flooring” Plan

Here’s a calm, low-drama plan that works in Ireland:

- Identify the subfloor (slab+screed, suspended timber, timber intermediate, apartment system).

- Measure what matters: moisture (RH test), flatness, bounce/deflection, thresholds, UFH presence.

- Confirm risk factors: radon area, ventilation strategy, wet room exposure. (EPA Ireland)

- Choose the floor + system, not just the plank/tile (adhesive, underlay, primers, movement joints).

- Budget for prep (it’s usually the real job). (fbsflooring.ie)

- Install with the building in “living conditions” (heat + ventilation stable), then maintain with mats, grit control, and sensible humidity.

If you want the choice to be straightforward, get a proper subfloor survey first. That’s how you avoid buying flooring twice. FBS Flooring can help you shortlist realistic options (laminate, SPC, engineered wood, click vinyl/LVT, solid hardwood, parquet/herringbone) once the subfloor facts are known. (fbsflooring.ie)

FAQ

- What’s the safest flooring for a new build with a young screed?

Engineered wood, tile, or glue-down LVT can all work — after the screed is proven dry enough and flat enough for the chosen system. Moisture testing (RH) is the key step people skip. - Can I install solid wood over underfloor heating in Ireland?

Sometimes, but it’s higher risk than engineered wood. Solid timber moves more with heat and humidity swings, so you need UFH-rated product specs, tight moisture control, and correct expansion detailing. - Can I tile over a suspended timber floor in a Victorian terrace?

It can be done, but not as a simple “tile on top” job. Timber deflection and moisture/ventilation must be addressed first, and the tile build-up needs to be designed for movement and stiffness. (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie) - What moisture level should my screed be before laying LVT or wood?

Follow the flooring and adhesive manufacturer’s limits, usually expressed as %RH from an approved test method. Many resilient floors target ≤75% RH, while timber often needs lower limits depending on system. - Do I need a radon barrier under my floor in Ireland?

It depends on the location and the building design. Ireland’s guidance addresses radon protective measures (membranes and, in certain areas, standby sumps). Use the EPA radon map and confirm your project’s radon strategy with your design professional. (EPA Ireland) - What flooring is best for apartments to reduce noise?

Carpet is often the easiest win for impact noise, but apartments usually require a certified acoustic floor build-up. Don’t change finishes without checking the acoustic specification and Part E targets for your building. (Government Assets) - How do I insulate a suspended timber floor without causing damp?

Keep the underfloor void ventilated, avoid blocking vents, and use a build-up that doesn’t trap moisture against timber. Traditional buildings often need moisture-aware, compatible solutions rather than “seal everything”. (nzeb.wwetbtraining.ie) - Is click LVT better than glue-down LVT on Irish slabs?

Click LVT is faster and can suit modest renovations, but glue-down usually feels more solid and handles heavy traffic better — if the slab is properly smoothed and moisture-compliant. Prep quality decides the winner. - How much does flooring installation cost in Ireland per m²?

Labour varies widely by floor type and complexity. Ireland-specific ranges cited by FBS Flooring put typical labour at roughly €15–€65/m², with levelling, moisture protection, trims and access often driving the final cost. (fbsflooring.ie) - What are the hidden costs that catch Irish homeowners out?

Levelling/smoothing, moisture mitigation systems, door trimming, thresholds, skirting decisions, and disposal. These are especially common in period homes with uneven floors and in new builds where screeds aren’t ready. (fbsflooring.ie)